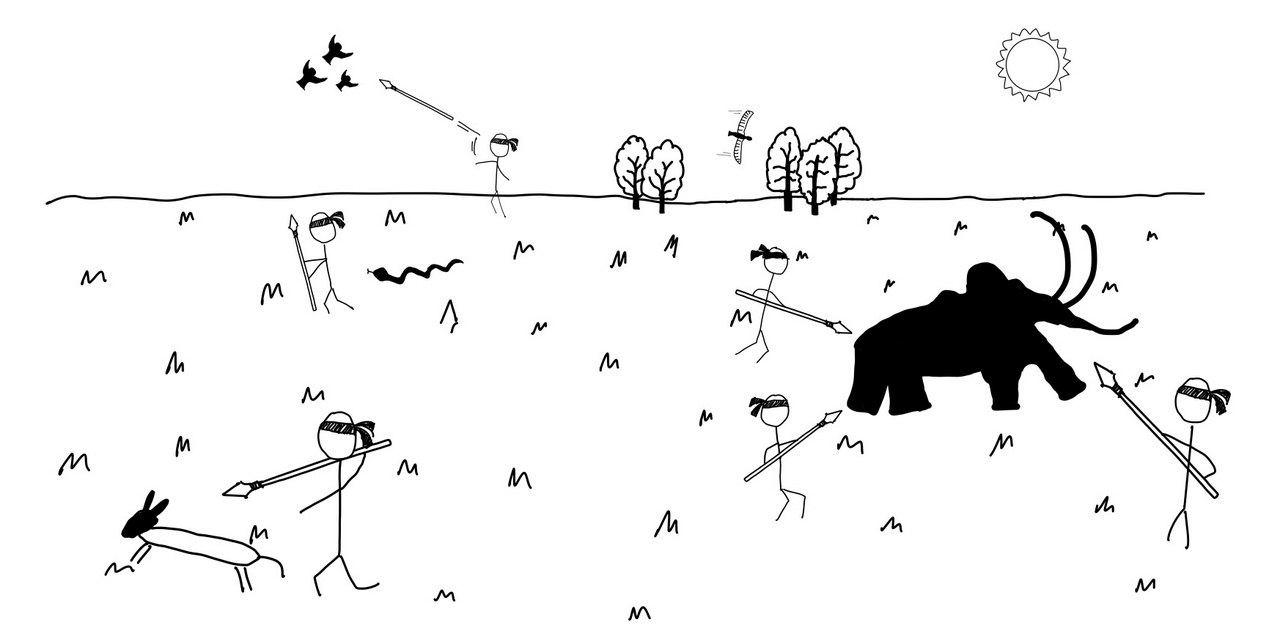

We are a bit like hunter-gatherers: each of us holds onto a spear that we use to work.

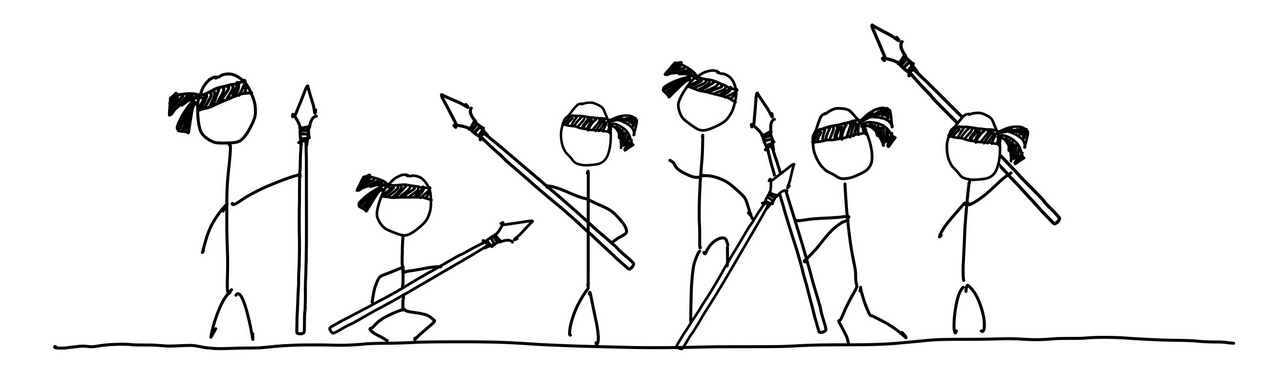

For the past year or so, we have used it to hunt all sorts of things.

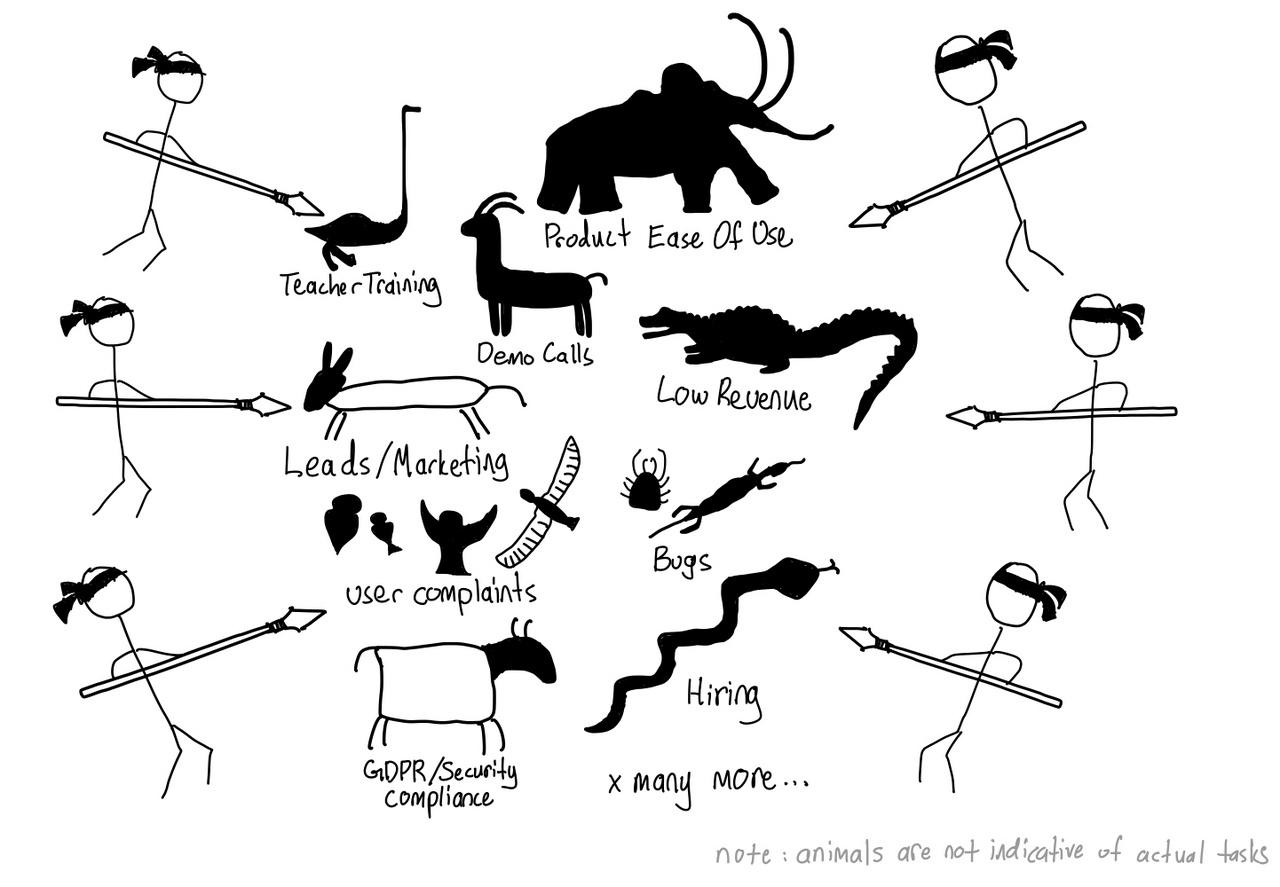

We have learned that there is a huge difference between hunting small prey and big prey: if we only hunt tiny insects, we will perpetually scramble for the next meal; if we hunt big mammals, we will naturally pursue greater hunts. In other words, small prey teaches us how to stay small; big prey teaches us how to grow big. Crucially, our energy comes from what we hunt.

There are plenty that can go (and have gone) wrong with each hunt: being unprepared, pursuing what isn’t prey, changing prey mid-hunt, or losing sight of the prey while hunting.

But more crucial than all these: where we point our spears.

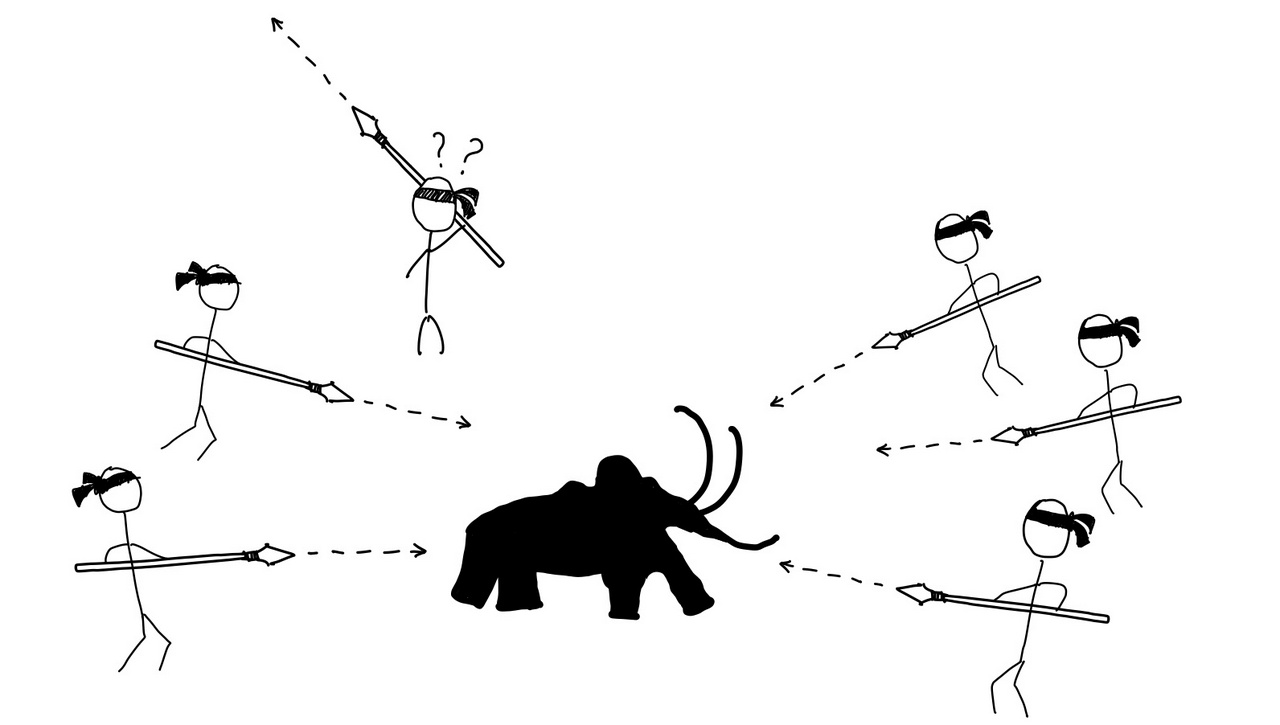

We should be wary whenever any of our spears are not directed at what needs to be hunted. This misalignment of spears may predict failure more reliably than anything else — a spear aimed at the sky or ground won’t hunt anything. Even a dull spear pointed at the right target stands a better chance than the sharpest spear pointed nowhere.

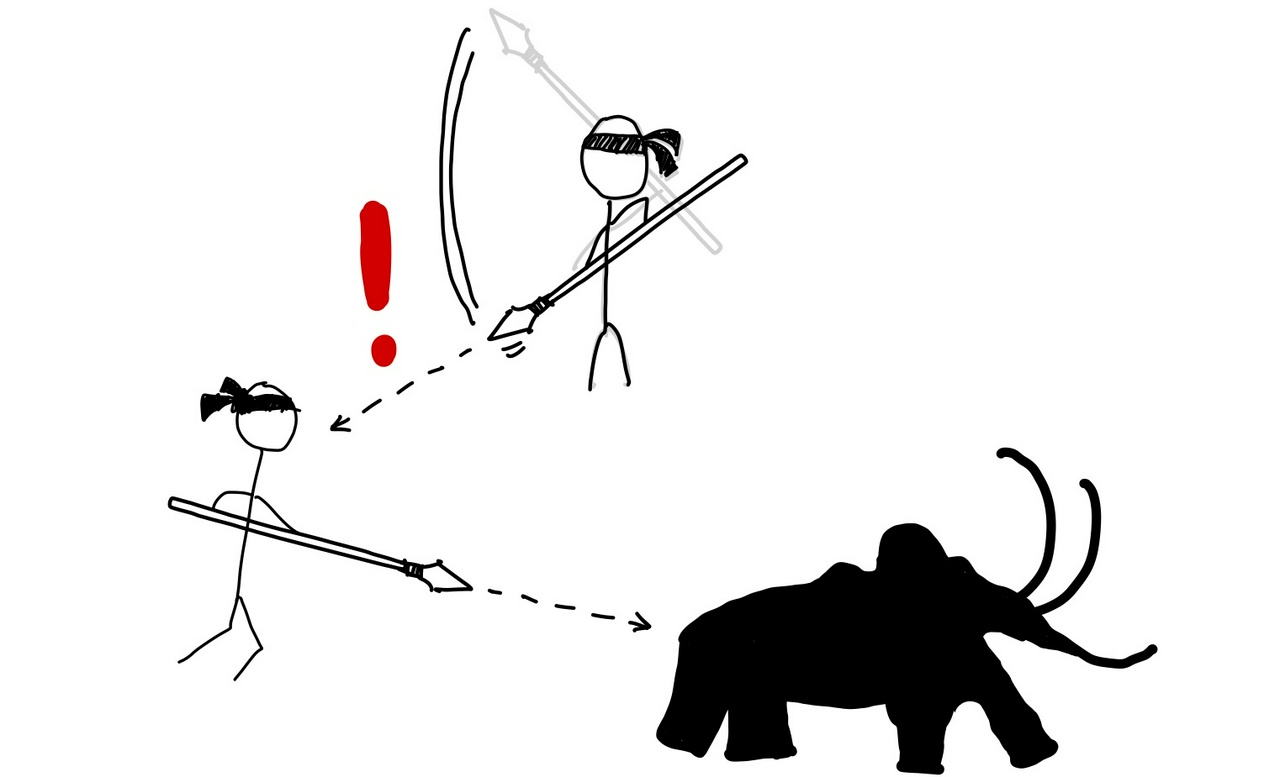

Yet, the real danger comes when the spear turns inwards, towards other tribe members.

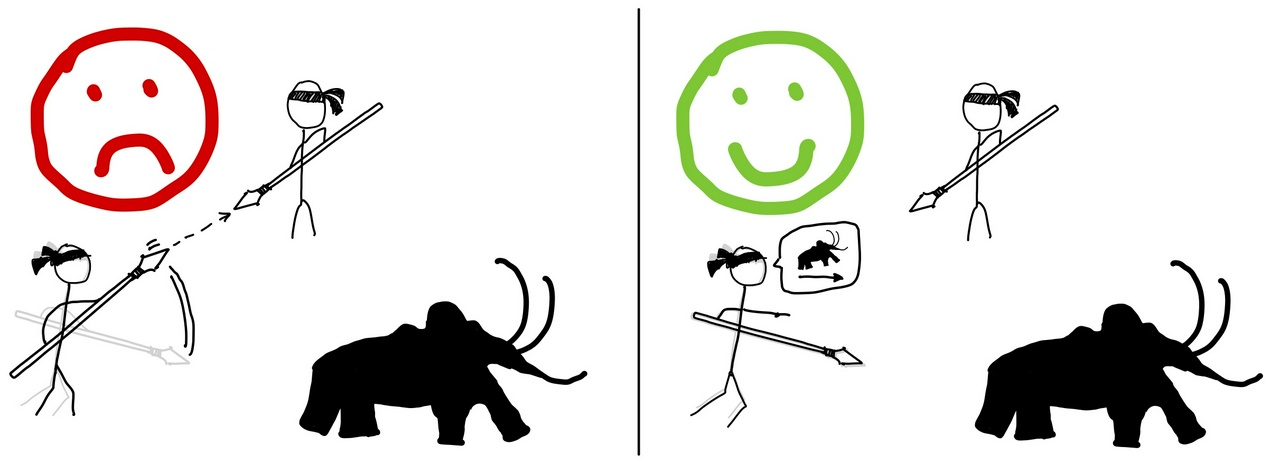

When this happens, it is tempting to point our own spears back. The way to correct a misaligned spear is not to aim another spear at them, no matter how strong the urge may be. This might fix the misalignment temporarily, but the underlying problem persists: each hunter’s vision of the prey determines where their spear will point tomorrow. If they do not see the prey we see, they will not align their spear with ours. More importantly, every time we respond to misalignment with spear-pointing, we teach the tribe that spears are how we solve internal, human problems. Our spears should point outward — to hunt, to provide, to bring energy to the tribe — rather than inward, towards our own people.

Do their acts stem from malice? It is difficult to say. But in the absence of a clear prey, spears will naturally drift — not necessarily from malice, but from the frustration and confusion of not knowing what to hunt. Sometimes, this drift turns dangerously inward, and we forget that we are hunters within the same tribe. A tribe starves not from the inability to hunt, but from the misalignment of their spears.

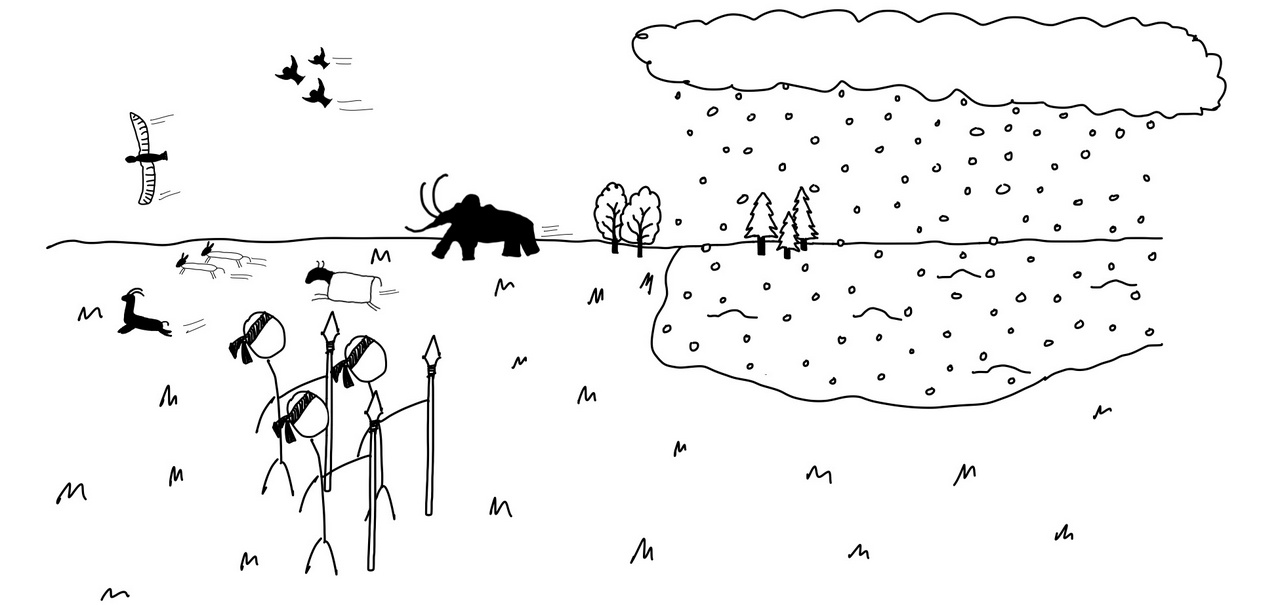

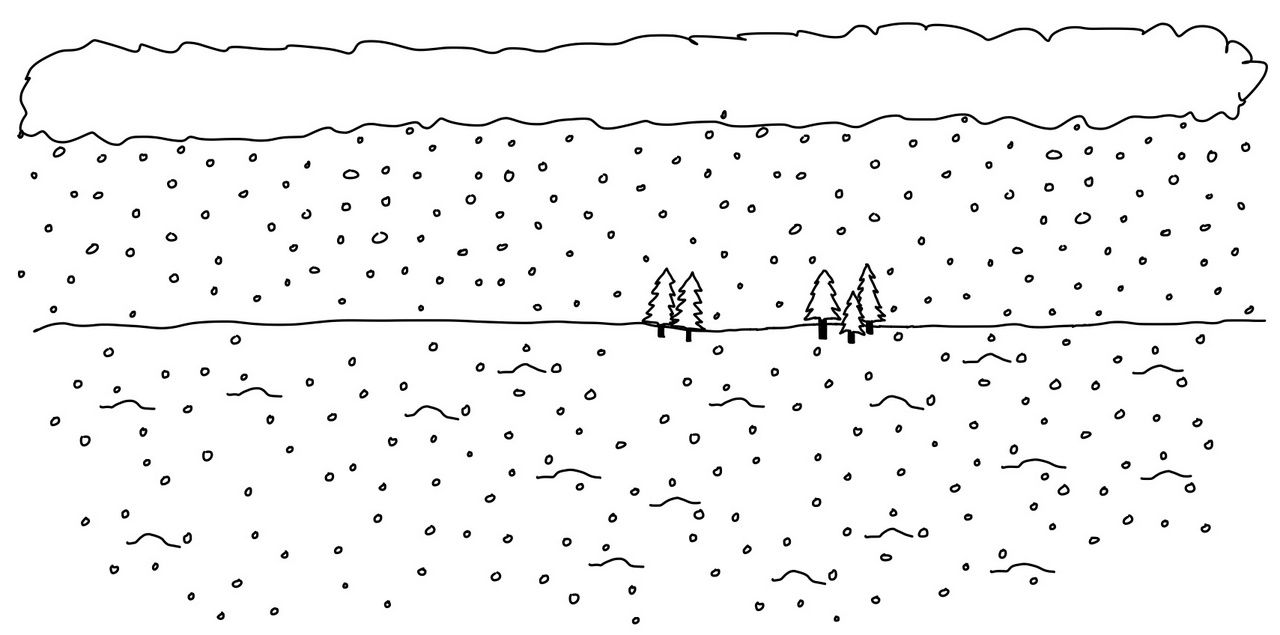

Yet, sometimes misalignment happens despite our best intentions, triggered by something no tribe can control: the changing of seasons.

When the season favors us, each hunt leads naturally to the next one. Our muscles remember exactly how to move, our hands know precisely where to grip, our spears find their target almost by instinct. The abundance of prey makes it virtually impossible to not know where to point our spears. Success breeds success, momentum becomes our greatest ally, and the tribe grows stronger with each hunt. In these moments, even the mightiest prey feels within reach.

Yet, if the season suddenly decides there is no hunting, then there is no hunting. No amount of prayers, rituals, or offerings can change this simple truth. Our great tribe of hunters mean nothing in an empty hunting grounds. Without prey, there is no energy flowing into our tribe. Our momentum disappears. Our spears, once guided by purpose, start to drift — and sometimes inwardly.

Perhaps different seasons simply call for different ways of hunting and living. What one sees as malice within a tribe may just be the quiet work of the seasons, slowly wearing down their spears until they lose their way.

Many tribes have died due to the turning of seasons.

But can survival be independent of the season? Can a tribe thrive in all seasons, or is mother nature too great to oppose? Perhaps thriving is too much to ask for. Perhaps some seasons are meant for sharpening our spears, for strengthening and upgrading, for preparing for the next hunting season.

In the end, it seems like it is not just the prey we hunt, but how we adapt to the seasons that defines the tribe's fate. Now, what will we do when the season changes again?